First posted after my trip to Poland in 2003, this post and The Story of a Shoe are posted today because today my youngest son, David, will visit Maidanek with a group of over 70 young men from his school.

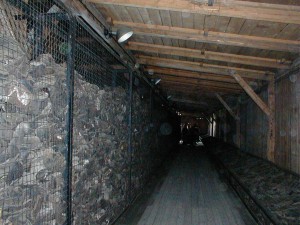

Maidanek is one of the easiest death camps to understand because there is little need to imagine. When the Russian troops swept into Maidanek in July, 1944, the Germans didn’t have time to destroy the evidence, as they did in Auschwitz, Treblinka, and elsewhere. Here the gas chambers remain, with the stained residue of Zyklon-B gas on the ceiling and walls. Here the crematoria remain, still filled with the ashes of the last victims. Here the ashes remain.

Because it is so intact, Maidanek is also possibly one of the hardest camps to visit. It is a place of death, and death lingers in the air, in the ashes, and on the ground on which you walk. You stare at the houses that are but a few hundred meters from the camp perimeter and you wonder what kind of person can make a life so close to such death. Homes and gardens surround the camp. They open their windows in the morning, and see the crematoria. They entertain friends and play music, in the shadow of the mountain of ashes. Once, they could have smelled the stench of burning bodies. The smell may be gone, but the air remains poisoned by the hatred. “What kind of person lives here?” I asked myself again and again.

As you walk into the crematoria, you see the table on which the Germans searched the corpses for hidden gold. Even in death, there was no dignity, no respect. You  walk into the room with the ovens and through the tears, the horror becomes more real because you understand that it isn’t dust piling inside the ovens, but ashes that remain, even 60 years later, to hint of their anguish.

walk into the room with the ovens and through the tears, the horror becomes more real because you understand that it isn’t dust piling inside the ovens, but ashes that remain, even 60 years later, to hint of their anguish.

Just as we entered the crematoria building, the skies opened. Thunder and lightening raged across the land that had been sunny just moments before. It was not difficult to imagine that this was the anger and the tears of a God who still cries for His children, and I wonder if some of those tears aren’t for those who still, even today, are murdered simply because they are Jews.

I thought of that shoe again and again while I was in Poland. Each shell of a synagogue we visited, each desecrated, over-grown cemetery, each building that to this day bears the trace of a mezuzah, the Hebrew lettering, the symbols of a religion and people hunted to the edge of extinction. Though the Jewish people as a whole rose up from this abyss, Polish Jewry did not survive. In the end, the story of that one shoe is the story of Polish Jewry. Destroyed, bereft, and unable to tell its full story.

Leave a Reply